Tolkien Chapter 5 - An Apologia that goes beyond Defense through Art

An Apologist, Who Never Apologized...Not With Blurb or Blurt or Bloviation, But only with Song

“...as with every art, every science serves God, because God is scientiarum dominus – Master of sciences – and docet hominem scientiam – Teacher of sciences to mankind” - Pius XII

"The true observer will study Nature because he loves her, and seeking neither reward not renown, will open his heart to her wonderful revelations.” - Maria Mitchell Citation

"Of star dust are we made and by starlight we live." - Canadian astronomer Allie Vibert Douglas

"I am on the side of the trees." JRR Tolkien

Tolkien was well-known as an enemy of the machine. As usual, the popular impression in this regard (and we will specifically discuss "Science"), is both accurate and misleading at the same time. Undoubtedly a "conservative", he was idiosyncratically and archetypally so: Margaret Thatcher might have appalled him as much as any Labor demagogue, and he was no believer in the automaticity of free market enterprise, geared and for hire as it was, with all of its machines that performed almost all our work. Adam Smith's "invisible hand", for Tolkien, might even be said to be that of Sauron himself. [In fairness to Adam Smith, I will note that not even he believed in a totally free market.]

Both Tolkien and Scott Buchanan shared an estimate of the machine and of Science as vulnerable to the forces of dark Magic, perhaps even a potential embodiment of them. Tolkien says the Machine "is more closely related to Magic than is commonly realized", in his letter to Milton Waldman. Scott Buchanan called Science "the greatest body of uncriticized dogma" we possess today, and likened it to "the Dark Arts".

Science, of course, as Tolkien must have realized, is just one approach, among several, to the human condition. To "machinify" man's worldview with the mandatory addition of particular Scientific paradigms then regnant, must have been enormously repugnant to a man like Tolkien. Art, Religion, and Philosophy, where were they, in the new House of Science? All too often, relegated to secondary status or even non-entities. If you think this is anti-intellectual, then you should read Jacques Barzun's House of Intellect: he crucifies Science, Art, and Philanthropy, in the name of Intellect. These three targets in modern form correspond (roughly) to the Idols of the Tribe, the Cave, the Theatre, and the Marketplace. Tolkien successfully avoided all of these. In our day, that means avoiding the religion of Scientism.

Tolkien begins the mythos of his world, not with a newspaper scientific account of a Big Bang (a "blurb"), or even the orthodox religious account in which God "blurts" the world into existence, nor yet the Philosophic "bloviation". Instead, he starts with Music and Song. We are thus treated, eminently, to an artistic account of Cosmogony:

Then Ilúvatar said to them: ‘Of the theme that I have declared to you, I will now that ye make in harmony together a Great Music. And since I have kindled you with the Flame Imperishable, ye shall show forth your powers in adorning this theme, each with his own thoughts and devices, if he will. But I will sit and hearken, and be glad that through you great beauty has been wakened into song.’

This pattern is repeated in the Garden of Eden with Man:

In “The Tale of Adanel” we read how the disembodied Voice of Ilúvatar spoke to the newly awakened humans with words quite reminiscent of Genesis: “In time ye will inherit all this Earth, but first ye must be children and learn” (MR 345) At first humans obeyed the Voice of their Creator, and as often happens, Ilúvatar’s human students discovered that “learning was difficult” (MR 345) and sought the easy and immediate answers from Ilúvatar himself. In response, Ilúvatar cautioned them to “First seek to find the answer for yourselves. For ye will have joy in the finding, and so grow from childhood and become wise. Do not seek to leave childhood before your time” (MR 345-6). As with most students thus addressed, the first humans became impatient and “desired to order things to our will; and the shapes of many things that we wished to make awoke in our minds. Therefore we spoke less and less to the Voice” (MR 346). Citation

If The Lord of the Rings is an artistic "apologia" (in the older sense of a defense), of what could it be said to defend or apologize for? I am using the word "apologia" even more broadly than the classical sense. A flower is a beautiful apology for a flower, as a beautiful woman is a good argument in her own favor, or as Paris is "always a good idea", both because good ideas flow in Paris, and Paris flows as many good ideas. A work of art is much more than a message. It cannot be merely a technical science, a literary critical philosophy, or even a cat's paw or dead hand for some kind of purely religious vision. As a made object it "stands for" something, but it cannot directly be "something else", nor just entirely for itself, for that would make it "Art for Art's sake", which is a religion of the Aesthetic. It can neither be a pure metaphor, nor pure self-instantiate. Art inhabits the shadow land between Reality and the pure Symbol. Art potentially moves through what Henri Corbin called the Imaginal World. That world, itself, is Art.

What follows is (admittedly) an amateur and layman explanation for material that could be very technically treated. I am endeavoring to be precise, but also, "common" in the best sense of the word. My justification for that would be the elite Vedic requirement for Truth, to be that which the wise man concurs with, but with which the commoner will not quarrel.

In order to be a great piece of Art, a work has to enter a very strange kind of dimension. It is difficult to guarantee exactly what the rules of this place are. As one man said, "I can't define pornography, but I know it when I see it." Mutatis mutandis, the same can be said of great Art, which of course LOTR is. Art is simultaneously philosophical, religious, and scientific, and yet not reducible to any combination possible of those three things. The potential of Art is greater than any mere combination of these three disciplines; integration is more than combination. Art has more scope than Socrates alone, St. Francis alone, or Sir Isaac Newton alone, or allied together, more scope for good or ill, beauty or ugliness, truth or lies. Art requires in some way the matter or material of these preceding disciplines, but in taking them up, wildly transforms them, qualitatively. Art amplifies the possibilities of the three, even taken together. Goethe's Faust, for instance, is not "merely" an apology for Western science, the Protestant Reformation, or existential philosophy. While it doesn't object to these things, it has a much more lofty agenda, which nonetheless manages to synthesize and include the others by subsuming them, integrally. LOTR accomplishes this on an impressive, world-building, participatory scale.

Greco-Roman world, then the Age of Faith, finally an Era of Science...an epoch of Art should be next. Link

To acknowledge that "Art is King (and Queen)" is absolutely not to associate Tolkien with any kind of Aestheticism, New Criticism, or modern day prophecy of the (for example) "World of the Image". A lot of prophecies, philosophies, and critical theories have advanced along these lines, a plethora, in fact, during the 20th and 21st centuries. They have tried to directly make Art, and to direct Art. They have turned Art into a cat's paw for various Leftist causes, ideological movements, or pseudo-scientific constructs. Alternatively, they have "vanished" Art by making it devour itself, for instance in pure Aesthetics, where the Art Object becomes something that merely justifies itself. The New Critical Movement embodied this new emphasis - Art, in order not to be a cat's paw or glorified Meme for Modernist cults, would withdraw into itself. Art would be gloriously isolated, and alone. It would cut itself off from its roots in Philosophy, Religion, and Science. Obviously, iterations, sub-iterations, and re-iterations of this cycle of controlling or castrating art can go on for some time, and arguably, Post-Modernism and Absurdism are the inevitable duality-oscillation of being stuck in this paradigm. Art, nevertheless, potentially integrates Philosophy, Religion, and Science, and is perhaps the only agent that can do this successfully, while preserving what it integrates.

Tolkien stood against (precisely) all of this. He was pre-Modern, but not anti-Modern in the sense of being opposed to creative novelty. The entire idea that these disciplines could be involved in endless turf wars was the great Lie, in his time, although it is still dominant (for a short while) in ours. No real creative novelty can arise from a deadlock between Science and Religion, or Philosophy and Science, etc. It is only possible to be creative if a synthesis is attempted. Analysis can yield much, but it is never going to yield synthesis. Synthesis, of course, is what LOTR, the undertaking of a synthesis, in Art. Tolkien represented a "going back" to an earlier unity, and then a "going forward" within that unity. This made him an idiosyncratic conservative, and a great artist. He was also the "last fruits" harvest (along with the Inklings), of a long chain of British and Anglo civilization, now seeming to close forever.

In getting at what Tolkien created (artefact), and showing how it avoids the problem of man-made artifice, hubris, and libido dominandi that might turn said artefact into a dangerous "Ring", we will turn to our own history in planet earth, or Varda (as he called it). History gives us the four fold cycle of philosophy, religion, science, and art, and Tolkien was nothing if not steeped in history. It was a part of his genius, and he steeped his own sub-artefact of "sub-creation" in Varda's own history to lend it verisimilitude, to increase the power of "suspending disbelief". A close reading (explication de texte) of the book of Reality, and of LOTR, will lead to something we can call "elective affinity" with Tolkien. I believe he set things up this way; it was a sign of this effort that he set LOTR "in the past" of our own earth, and linked the world to myths of Atlantis. See also, here.

Tolkien's strategy was entirely practical and concrete. It was as concrete and tangible as the statue of Western Latinate Christianity, or the icon of Eastern Latinate Christianity. Both the statue and the icon are "windows" to something higher than merely human religion. They are religious artefacts, but more. Since artefacts, they therefore draw upon Science; they are the products of theological wrestling, and therefore draw upon Philosophy. They are devoted, much more obviously, to the service of Religion, but the civilized history of all mankind in Philosophy and Science enter into the background of the statues and icons of ancient Christianity, as well as the temples and the cathedrals which house them. It is not possible to fathom the meaning of a Gothic Cathedral or a wonder-working Icon without appreciating that Greek philosophy and nascent Science contributed to their creation, or at least, without sharing that same dimension, albeit unknowingly. Scientists may well opine that a cathedral has nothing in common with a nuclear reactor, and they are right in at least one sense. For the cathedral is putting atoms together creatively, rather than tearing them apart.

A genuine classic - it's worth knowing the spiritual depth behind the Cathedrals, besides visiting them (which is more important)

There is a legitimate analogy, here, with Science in the infinite exploration of infinity, presented in comforting and condensed form, without the sacrifice of inner expansion, inside the Gothic cathedral. In the space of the cathedral, one is confined, but set free. The same thing can occur out doors, in the cathedral of Nature, or in the library study:

“I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.” - Sir Isaac Newton

Philosophy, Religion, and Science are all efforts to bring man into view of the ocean of Truth. Art completes the cycle by dint force (magically and beautifully and seductively applied) of synthesis and harmony. And in fact, this is precisely what we encounter in Tolkien's chosen word and world of Mythopoeia. Mythopoeia is the artistic rendering of religion (myth) as a "making" or poem. Tolkien is at pains to point out that philology (Science) and words co-evolved with story telling. Once you bring "craft" or "making" together with Religion, it is difficult not to talk about both Science and Philosophy. This is because the "making" is anterior to either formal Philosophy, organized Religion, or disciplined Science. It is the possibility space out of which the others arise.

That the images are of things not in the primary world (if that indeed is possible) is a virtue, not a vice. Fantasy (in this sense) is, I think, not a lower but a higher form of Art, indeed the most nearly pure form, and so (when achieved) the most potent...Philology has been dethroned from the high place it once had in this court of inquiry. Max Müller's view of mythology as a “disease of language” can be abandoned without regret. Mythology is not a disease at all, though it may like all human things become diseased. You might as well say that thinking is a disease of the mind. It would be more near the truth to say that languages, especially modern European languages, are a disease of mythology. But Language cannot, all the same, be dismissed. The incarnate mind, the tongue, and the tale are in our world coeval. Link

Christianity usually took this angle of tact with the demigods. There may have been other legitimate tacts. - Boniface felling the oak of Thor in Saxony. Citation

Mind...tongue...tale. In the mind, we have philosophy, in the tongue religion, and the tale, science. But Tolkien wished to make these three dance, and live, together. For many generations of European intellectuals, this had not been the case. Andrew Dickson White bears a heavy burden, along with others, in constructing the narrative of A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom. Such narratives prove Tolkien's insight - it is the "telling" which breaths life or death into the inquiring dance of man's spirit and mind, a right that (according to Tolkien) has "not decayed, used or misused". Another example would be the classic dichotomy between "fact" and "value", a narrative (one could say, habit) introduced to the modern mind by men like Max Weber. These are analytical distinctions, and not (by themselves) a practice of the synthetic method, or Mythopoeia.

Where in Middle-earth, one might ask, are we treated to anything like "Science"? More cynical sceptics may say, where is the "Religion" or "Philosophy"? The argument I am making is that we are treated (in Tolkien's mythos) to all three in an Ur-form. This Ur-form is the condensing and then expansive power of Art, to both destroy and transform and re-create all three. We can even relate them to the qualities enumerated by Tolkien of Recovery, Escape and Consolation (in the essay, On Fairy Stories). Although great Philosophy, Religion, and Science properly do all three of these, the emphasis in Philosophy is arguably on Escape, the emphasis on Religion on Consolation, and that of Science on Recovery. Others may arrange that differently, but they correspond to the paths of Wisdom, Love, and Power (which also can creatively change places in arrangement).

Let us see what we can find to support our thesis, in Tolkien. We will start with the most difficult one, that of Science. Science is in LOTR, well represented and sturdily encountered, through the dwarves. The "urge" of Science is embodied in the dwarves. This is the Ur-principle of Science: the urge to take hold of Nature and "question it", forcing it to yield up secrets. "If something is technically sweet, you do it," noted Robert Oppenheimer, who helped build the atom bomb. The Dwarves would have agreed.

The entire history of the Dwarves, their bent or proclivity to this end, is embodied in the story of their "making" as a race. Their epic "pre-history" came about because they were awakened "too early" in the process of Creation, and began to "delve too deep" into the minerals of the earth. Aule was barely second to Melkor in skill, and Melkor envied him. The same theme will affect Aule, but not as greatly, as banished Melkor:

Aulë, the craftsman – or engineer – of the Valar, was given by Ilúvatar “skill and knowledge scarce less than to Melkor,” a particularly ominous connection (Sil 19). Unlike Melkor, Aulë freely gave the fruits of his skills to others and delighted in the process and outcome of his labors rather than in possessiveness and hubris...Citation

Like Melkor he was a craftsman, a smith. One of his Mairon went over to Melkor, and later became Sauron. The Dwarves, of all the races of Middle Earth, went the farthest in mining, forging, splitting and recombining, attaining the power of the "artifice" from the new born fires of Creation. It was they who embodied the sturdy, inquisitive, and hand-crafted investigation of roots of Arda, her minerals, her deep and dark places, her inner secrets.

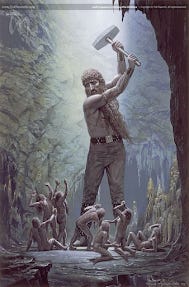

Link - Aule jumps the gun with Science - and so the dwarves are good at it

Aule pre-created the Dwarves, and did not wait for the children of Iluvatar. He quickly repented, and submitted his children to Iluvatar's will. Iluvatar adopted the dwarves, but they were put to sleep, to wait for the right time.

Upon fashioning the seven dwarf fathers, Aulë was visited by the Voice of Ilúvatar and faced the failure of what he had attempted to accomplish: “Why dost thou attempt a thing which thou knowest is beyond thy power and thy authority? For thou hast from me as a gift thy own being only, and no more” (Sil 43). Demonstrating his infinite love and pity, Ilúvatar adopts the dwarfs and gives them the autonomous spirits (souls) that Aulë does not have the power to bestow.

The dwarves embody both the course of human science by being impulsive to discover the secrets of Nature, and the fate of the fairy creatures (the Fey), by being separate from the true children of Iluvatar and on a parallel course of evolution. The Fey, of course, are heavily discussed in Tolkien's seminal essay on Fairy Tales. Tolkien makes it clear that the Fey "control" Nature in powerful and important ways that are mesmerizing to humans, and can suck them into an illusion that seems real, to the potential danger or discomfit of the human race. The magical term for this is "glamor". CS Lewis also discussed the Fey in his The Discarded Image, under the name of the Longaevi.

Although overt magic and glamor is more often associated with the High Elves in Tolkien's world, my point here is that the "making" or artifice in natural magic is pioneered by the dwarves, because it is semi-scientific and systematic. The dwarves perfect this aspect of magic, its attention to cunning craft in the cleverly made artefact. They delve, they craft, they explore the fabric of the Cosmic Egg condensed as Arda, the primal Earth. They are smiths. When the high elves craft the rings of power, they are imitating the dwarves. They have brought dwarvish craft to bear upon elvish concerns. Smith-working was begun by the race of dwarves. Magic began as song, but was disintegrating into technology. The Elves, by contrast, hold more to the Natural (right) course.

I don't recall the Dwarves doing much with gardens. Thawdor Castle in Scotland.

Similarly, in a letter to Michael Straight, Tolkien explained that The Elves represent, as it were, the artistic, aesthetic, and purely scientific aspects of the Humane nature raised to a higher level than is actually seen in Men. That is: they have a devoted love of the physical world, and a desire to observe and understand it for its own sake and as ‘other’ – sc. as a reality derived from God in the same degree as themselves – not as a material for use or as a power-platform. (Carpenter 236)

Yet what would Middle Earth be without Dwarves? And what would Man be, without Science? Even as the great arcana arise, there is a necessary "muting" towards Philosophy, Religion, and Science, in Tolkien's artistry, across the board. But in his artefact, Despite the "muting", the influence runs in both directions. This is what makes the work "mythopoeic".

Luc Vivès and Christine Argot remark that “Tolkien’s work is unique in that it forms the first interface between cycles, sagas, and epics on one hand, and nomenclatures, dictionaries, and encyclopedias on the other […] coming as close as possible to being a study of the natural world perceived mythologically, and mythology perceived as natural” (p. 277) Citation).

For we note that, this doesn't destroy the three great disciplines, but rather, sets them on the path of a re-blossoming: they will be recovered (Wisdom), consoled (Love), and escape (Power). In LOTR, just as there is no pure human Science, so there is no real human Religion (or elvish for that matter), nor no "real world" equivalent to Philosophy, per se. There are only magical analogues, an "essence" or "seed" of the future tree. "They are re-mythologized, in an age that is otherwise de-mythologized" (Personal notes from Critical Theory Class at Hillsdale, Dr. Daniel Sundahl). Knowing these three disciplines only in their secular form, we necessarily have trouble recognizing the "seed" or "form".

We can feel confident to establish, then, that in LOTR, and mythopoeically, the Dwarves are an important analogue for the "making" of Science. Of course, in some telescoped sense, Tolkien himself is "digging" and "delving" and "making", just like the dwarves. He participated, as Author, in his own story, in the pre- but also the Ur- mode of Science. The LOTR is, in some sense, an artefact that parallels "The Ring of Power". This (like Science) is a "right" that can be "used" or "misused". In telling LOTR, Tolkien accomplished a taking apart of the world, and putting it back together, gaining knowledge along the way. This knowledge or gnosis is not anti-scientific, but pre-scientific or proto- or Ur-scientific, being an energetic and living recapitulation of the analysis and discovery principle we find in the history of Science.

Despite being opposed to the "Machines", Tolkien can in no way be considered an enemy or opponent of Science. It is clear that he thought naked Science (or Scientism) incomplete or even degenerate. This is hardly surprising, once one undertakes the correlation of Philosophy, Religion, and Science through the power of Art. Any of these three alone - unbalanced - would constitute a kind of tyranny of incompleteness. In Science's case, "technique" would come to justify itself without reference or eye to the participatory process of Creation. The Nazi scientists may have been horrid humans, but they did legitimate Science. I am tempted to argue that Tolkien may have been a terrible professional scientist (he never claimed to be or aimed to become one), but because of his humane qualities, did good work for "Science". In setting up legitimate inspiration and mythical justification for the qualities of joy, discovery, and creative analysis, he is contributing to what can be called the elemental urge towards Science, in human nature.

Similar analogues to both Ur-Philosophy and Ur-Religion could be pointed out in LOTR, but I do not intend to rehearse them at length here. As Jonathan McIntosh goes to great lengths to prove, in The Flame Imperishable: Tolkien, St. Thomas, and the Metaphysics of Faerie, the form religion takes in LOTR is adequaetio or commensurate with the stated nature of Iluvatar, the Creator. McIntosh's work is a tour de force, but this is the culmination of long effort in Tolkien studies. While Tolkien was still living, in the 1950s, William Ready had already noted what McIntosh (and Verlyn Flieger before him, less openly) later brought to full light:

Artists are didactic, but for the mind they seek to move this must now show, for it makes their work suspect, and perply so. One of the great things in facor of Tolkien, in the opinion of many of his readers who have rejected formal religion, and they are in the millions, is that there is no religion in the Lord of the Rings, though, in fact, it is all Religion. The story can be read for pleasure and the book closed; what happens after is within the reader. - P.53, William Ready, The Tolkien Relation - A Personal Inquiry

A clear progression in Tolkien Studies...

The elves seem to gravitate or embody the urge to Religion, while the age of men lays more emphasis on counsel and thought, or Philosophy. Rather than look for any of these three disciplines in their final, disciplined, and modern form, we can find all of them muted and transfigured in the Art form of LOTR. Tolkien is attempting to "prove" his thesis, by demonstrating it artistically. Overdeveloped Science in LOTR leads straight down the slippery slope, from Melkor, to Sauron, to Saruman. Yet,

Ordway writes,Tolkien objected strenuously to the abuses of technology, but did not find technology to be evil in and of itself. As he reminds the reader in “On Fairy Stories,” when discussing the genre of fantasy, abusus non tollit usum (abuse does not preclude proper use). His opposition to the machine age was qualified, more so than is often supposed. For example, in the BBC interview referenced above, Tolkien offered surprisingly responses to questions about industry (I’ve no objection to that as such”) and factories (“They might be better than they are. It depends on what you mean by a factory, I mean a factory may be a very big or a very large, or very small thing”). Given the opportunity to criticize industry and technology as extravagantly as he liked, he chose a sober response. (Holly Ordway, Tolkien’s Modern Reading: Middle-earth Beyond the Middle Ages - Link)

It was the abuse of the machine, or "technique", which he loathed, not Science per se.

Despite what you might have been told or read online, Tolkien was not antiscience. On the contrary, he reported in his famous essay “On Fairy-stories” that as a young child “a liking for fairy-stories was not a dominant characteristic of early taste…. I liked many other things as well, or better: such as history, astronomy, botany, grammar, and etymology” (Flieger & Anderson 56). In other drafts of the essay he notes that “In that distant day I preferred such astronomy, geology, history or philology as I could get, especially the last two” and that as a young child “I was ready enough to study nature scientifically – very ready, quite as ready as to read fairy-stories. But I was not going to be quibbled into science nor cheated out of Faerie” (Flieger & Anderson 189; 234). As a citizen of both of C.P. Snow’s cultures, Tolkien was able to recognize and appreciate the beauty and value in both points of view. This synthesis is most apparent in his description of his chosen academic field, philology, defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “the branch of knowledge that deals with the structure, historical development, and relationships of a language or languages.” In a 1964 letter Tolkien explained “I am primarily a scientific philologist. My interests were, and remain, largely scientific” (Carpenter 345)...“Of course my story is not an allegory of Atomic power, but of Power (exerted for Domination).” In a 1951 letter to Milton Waldman, Tolkien further explains that the Fall of humans in his works (and, by analogy, in the real world) occurs when the sub-creator (or engineer, in a technological sense) wishes to be the Lord and God of his private Creation. He will rebel against the laws of the Creator – especially against mortality. Both of these (alone or together) will lead to the desire for Power, – for making the will more quickly effective, and so to the Machine (or Magic). By the last I intend all use of external plans or devices (apparatus) instead of developments of the inherent inner powers or talents – or even the use of these talents with the corrupted motive of dominating: bulldozing the real world, or coercing other wills. The Machine is our more obvious modern form though more loosely related to Magi than is usually recognized. (Carpenter 145-6) .

Philosophy and Religion, often in the LOTR, merge together, in and out of each other. As with Science, the corruption of Philosophy and Religion are more in evidence, than actual modern disciplines, per se. When Religion with a capital R, organized Religion, comes to Numenor, it is in the form of horrid, corrupted rites that desecrate altars the moment they are raised.

But Sauron caused to be built upon the hill in the midst of the city of the Númenóreans, Armenelos the Golden, a mighty temple; and it was in the form of a circle at the base, and there the walls were fifty feet in thickness, and the width of the base was five hundred feet across the centre, and the walls rose from the ground five hundred feet, and they were crowned with a mighty dome. And that dome was roofed all with silver, and rose glittering in the sun, so that the light of it could be seen afar off; but soon the light was darkened, and the silver became black. For there was an altar of fire in the midst of the temple, and in the topmost of the dome there was a louver, whence there issued a great smoke.

To look for organized Religion, formal Science, and official Philosophy in LOTR is to hunt for the Snark. Rather, one sees them blended, and mythopoeically revivified, in their essential forms together in a dance, which is the Art. In much the same way, had one traveled backwards in time to the birth of Faustian Europe in the Gothic, one might have taken the treatises of Pseudo-Dionysius, the Western religious rite, and the speculations of Robert Grosseteste as simultaneously present and yet distinct, blended to synergize something higher than all three, in the emerging architectural form. And in fact, that is exactly what happened, historically. Tolkien is, to all intents and purposes, both a man of his time, and yet also capable of going back to what Oswald Spengler called "the Springtime Forms" of his own civilization.

A manuscript of Grosseteste, bishop of Lincoln, showing refraction of light in water.

Therefore in LOTR, and in the creations within LOTR, there is a kind of pure human Art. In fact, LOTR possesses more pure Art than our own world. And our thesis explains this, beyond the fact that it is "fantasy". Gondor, for instance, is a city built to appeal to a lover of Art. Rivendell, Lothlorien, even the Shire, are prima facie exemplars of Art. Only analogues of philosophy, religion, and science can be found in Middle Earth, but Art exists in a pure form. One might say, in the purest form, as the combination of the former three disciplines.

Tolkien's genius was to intuit that this pure form of Art transcended, but also sublimated by assumption of those prior forms into itself, the preceding conditions. Nonetheless, this did not occur in a vacuum, since Magic enlivened the whole and carried it into a place which touched upon the subjects it transcended or transfigured. There is much thinking about human love of wisdom, searching for God, and desiring to know, all throughout his epics. This is what separates Tolkien's project, from (say) the Theatre of the Absurd, New Criticism, or even more so, Critical Theory of any kind. There is no suggestion, in Tolkien's work, that we can go out into the street and "make the revolution", or that "raising consciousness" of any existing human orders can bring about a magical world, or even that we can retreat into the world of Middle Earth, there to merely contemplate a making that explains itself, without reference to the actual world.

LOTR does not "explain itself" - for that, you need the background of the Silmarillion, and the cosmogony of the Ainulindale. Above all, one needs the doctrine of God as "Being-in-itself", which is what Iluvatar is, in the art form. LOTR stands within itself, when it does, because it is already related to "real" Reality. Within this backgroundit invites an explanation, without demanding one. It recapitulates the myth and art of all the previous eras, just as it recapitulates the texture and quality of Tolkien's own mind and making. It is simultaneously as escapist as it could be, and as rooted in reality, as it can be.

Temple of Melkor, Ted Nasmith Source

To return to our initial analogy, the statue in the West, or the icon in the East, recapitulates all divine knowledge that man has acquired from philosophy, religion, and science, summing it up in an enduring art form. As a large generalization, Northern Europe modified the statue to build the Gothic Cathedral, while the East preferred to endure with the initial chosen form of Ikon, but it is well established by scholars that each form was not only not opposed to human knowing and disciplines of the sciences, but rather incorporated and transfigured them. The intellectuals may dispute this, the scholars do not. Erwin Panofsky, for instance, argues that the Gothic Cathedral was built on a scholastic super-structure. Adding to his point, this would later manifest as the great investigation into empirical nature. Jacques Barzun in his tome, Science: The Glorious Entertainment, shows us the artistic side of that scholastic impulse that came to fruition through medieval science. There is a deep synchronicity and inter-connectedness, manifesting and enabled in Art, between the disciplines of various sciences.

Understanding the "cosmogenesis" of our own modern world more deeply, it is possible to realize that we are confronted with an angular uncomfortable fact. The "relic" or artefact of making, what we tend to think of as byproduct of Progress, is actually a central point of the whole exercise. Sir Isaac Newton's "smooth pebble" or "prettier shell" becomes an exercise in a process that is both terminating and self-contained, and yet a living and moving form of something that will go on and on. It is distilled natural Magic. It is simply not possible to say, within the world of LOTR, whether Nargothrond was "worthwhile" in the making, or if the Rings of Power were "worth it". To ask this, is to miss the point of the exercise. The history of Middle Earth (including its tragedies, its brutalities, its despair) is part of the artifice, and therefore Art, of the Creator. They have their place, and will receive their "hour". In the eschaton, Tulkas will wrestle and Melkor, but is Turin (a man and a hero) who will then slay him. Turin will be redeemed.

1 Corinthians 8:5: "For though there be that are called gods, whether in heaven or in earth, (as there be gods many, and lords many,)" - St. Paul Image

Tolkien is applying this, analogously, and most uncomfortably (or delightedly as the case may prove), to our very own, very "real" world. Tolkien actually believed in the power of fairy stories to recover, to escape, and to console. Both Paul Tillich and JRR Tolkien served in the trenches of World War I. Whereas Tolkien seems to have recovered, escaped, and been consoled, Paul Tillich did not. Estrangement (Entfremdung) or alienation was the keynote of Tillich's life and thought. Tolkien, on the other hand, followed a "There and Back Again" path, which involved returning to his primordial state of comfort. Moorcock and others like Edmund O. Wilson, have attacked Tolkien for this, as we investigated in Chapter 4. Our argument has proceeded from the relationship of the lesser to the greater.

That is, given that Tolkien has necessarily human foibles (the presence of the Shadow, as JM Greer argues), and conceding all contestable ground to critics, why is it that his art is still so consoling, escaping, and recovering? Did Tolkien understand the one thing necessary, which renders his Art impervious to objections, no matter how valid? If an artist succeeds in establishing a living link between the lesser and the greater, such that one can argue in either direction, to defend that Art, does this survive all objections? If Tolkien's world evokes the True, Beautiful, and Good, it follows that his foibles are overcome. If his foibles overcome themselves, it follows that the Art evoked will be True, Beautiful, and Good. That is, the Art will be Substantive, Pleasing, and Useful. Everything else, as they say, will fall in between, and tend to be subsumed in the artistic process. The natural Magic is to mimic Reality, only to discover that Reality is already mimicking itself. At that point, the objet d'art or made artefact becomes potentially as "natural" as Creation itself. Especially if the sub-creator is aware of this irony.

Role-playing in Middle Earth - a participatory form of Art and Knowledge...

Tolkien did not bother much with explicit and abstract theories of his art or philosophy or religion, and it is not the purpose of this book to bother much with them either, except to demonstrate that his interest in the process of "telling" or "weaving" hides a sophisticated and powerful understanding of how Reality works. The cynical emphasis today in critical theory on "narrative" demonstrates how powerful words and stories can be. They learned the lessons Tolkien knew already about stories. Critical Tolkien scholars construct rival narratives (counter spells) about Tolkien.

The Chapel of the Holy Blood, Bruges : Christian temples in Faustian Europe are different... unique

The completed and well-crafted Art Form, however, stands outside psychological, ideological, and secular critiques. It "stands alone" not as an abstraction, but as something concrete and mysterious which points like a finger, to the moon itself, source of new beginnings within a beginning which has no end. An Icon/Image anticipates critique by incorporating the artful side of philosophy, religion and science, activating in this manner, the latent human powers of natural magic present in the imagination. In the well-crafted tale or telling, the Art Form wraps itself in a human showing that generates an objet d'art which, for all practical purposes, is a form of theurgy. This statue comes to life, rather than in the critiques of its detractors, in the mythopoeic realm of imaginal images. The process is neither arbitrary, mystifying, nor obfuscating. It is a species of enchantment, or re-enchantment. Here is a poet, operating under its spell:

I feel a long and unresolved desire

For that serene and solemn land of ghosts,

It quivers now, like an Aeolian lyre,

My stuttering verse, with its uncertain notes,

A shudder takes me: tear on tear, entire,

The firm heart feels weakened and remote:

What I possess seems far away from me,

And what is gone becomes reality.

Prologue to Faust, Goethe

I am tempted to argue that Tolkien does not so much fall prey to reactionary politics, shadow-projection, & ideology, as he effectively gives us a magical means of redeeming them. It would be a redemption, since Tolkien's worth shines in very spite of such a redoubtable potential fault. After all his critics have had their legitimate say, and their criticism can give us much in other regards, and perhaps even in Tolkien's. Yet it remains to be noticed that the target of their criticism has emerged unscathed, or even re-invigorated, for what remains is the residual purpose and essence, which is unreducible.

The Squirearchy (Religion), the clumsy Shadow (Philosophy) work, and the Ludditism (Science) of Tolkien represent the essential, beautiful, and useful Good which is operative in spite of, perhaps even because of, those elements or forces. Whether it is a Ring to be destroyed, or passed into the West, was up to Tolkien's craft. It is in Tolkien's mind in which these elements are granted redemption, and the enduring world of LOTR shows this. His mindshares this telling in such a way, that critics are forced to quarrel with its irreducible presence. So much for the critics, if they cannot reckon or wrestle with Tolkien's redemption of the values of "The Shire". I will note that at least one of them (John Michael Greer, whose criticism is both the sharpest and most even-handed) concedes that LOTR is likely one of the few works of modern times read more than a thousand years from now.

One does not quarrel with a cathedral or an icon. One can only attack it and destroy it. Because the incarnated Art binds up of philosophical, religious, and scientific energies within an Art Form to such a degree, that it distills a kernel or essence powerful enough to become operant in the mythopoeic universe of the imaginal. Oswald Spengler, if one prefers a secular example, goes some way to showing how this occurs at the level of the Great Civilizations. You cannot quarrel with the Sphinx, the Giza pyramids, or the halls of Osiris. They embody the fundamental kernel of a vast panoply of various arcane and semi-arcane disciplines, such as Egyptian philosophy, religion, and science can be intuited to have been. They artistically show us the invisible and simple idea behind a Great Civilization, just as Euclidean geometry, Greek temples, and Platonic dialogues grant to us a glimpse of the invisible posture of the great form behind Hellenic culture.

Phidias exhibiting his art work: the Imaginal and the Liminal go together...

One does not have to accept Henri Corbin's full blown, esoteric defense of the Imaginal World to understand that classical music or Gothic cathedrals or the French encyclopedias operate along a liminal borderland which makes the invisible partially visible, to even non-believing human intellect. This state of affairs has been (I maintain) denied by the intellectuals, but affirmed by all the sages and scholars. A list could be compiled, none of it particularly arcane or controversial. Lubicz's monumental The Temple of Man is a prime example of such. George Duby's the Age of Cathedrals: Art & Society 980-1240., does something similar for Gothic civilization, as Lubicz did for the ancient Egyptian. The Hellenic artist Phidias, Oswald Spengler argued, summed up the inner high point of Greek civilization in art. He gave it all, in a nutshell, and works like these do the same thing: they establish the pellucid connection between those highest and most perfect works of art, and the civilization that made them possible, by artistically summing up the inner and invisible idea, behind both of them. Thus, Goethe's Faust (as it were) explains "the nature of things" for Western Man; it gives the "way of things". Through the work of art, as through the high culture, the visible and invisible begin to trade places. A transposition between art and culture also occur.

Here the Cultures, peoples, languages, truths, gods, landscapes bloom and age as the oaks and the pines, the blossoms, twigs and leaves - but there is no ageing “Mankind.” Each Culture has its own new possibilities of self-expression which arise, ripen, decay and never return. There is not one sculpture, one painting, one mathematics, one physics, but many, each in the deepest essence different from the others, each limited in duration and self-contained, just as each species of plant has its peculiar blossom or fruit, its special type of growth and decline...Scientists are wont to assume that myths and God-ideas are creations of primitive man, and that as spiritual culture “advances”, this myth-forming power is shed. In reality it is the exact opposite, … this ability of a soul to fill its world with shapes, traits and symbols - like and consistent amongst themselves - belongs most definitely not to the world-age of the primitives but exclusively to the springtimes of great Cultures. Every myth of the great style stands at the beginning of an awakening spirituality. It is the first formative act of that spirituality. Nowhere else is it to be found. There - it must be...The Apollinian [classical Greek] Culture recognized as actual only that which was immediately present in time and place-and thus it repudiated the background as pictorial element. The Faustian [modern Western] strove through all sensuous barriers towards infinity-and it projected the center of gravity of the pictorial idea into the distance by means of perspective. The Magian [Byzantine-Arabian] felt all happening as an expression of mysterious powers that filled the world-cavern with their spiritual substance-and it shut off the depicted scene with a gold background, that is, by something that stood beyond and outside all nature-colours. Gold is not a colour. - Excerpts from Oswald Spengler, Decline of the West

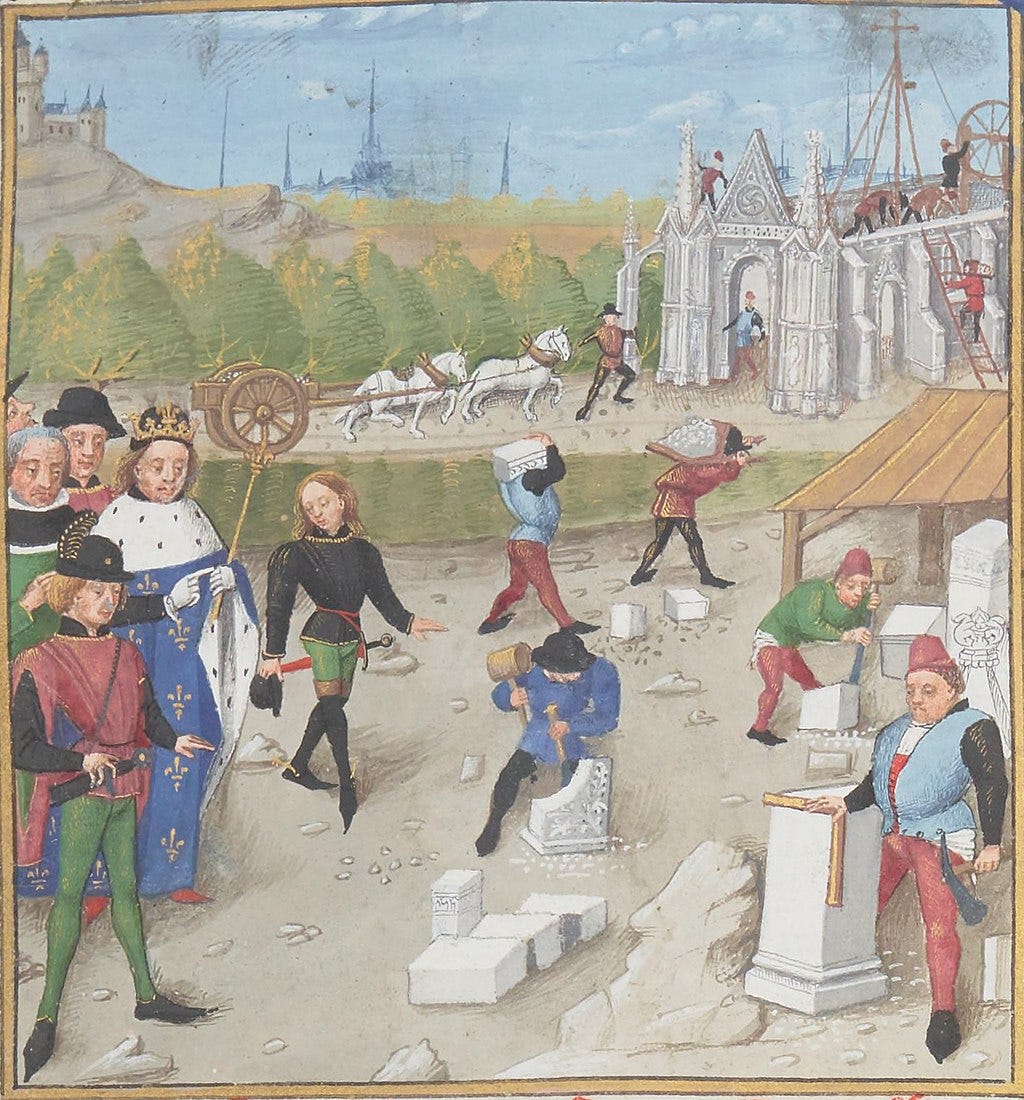

Dagobert I building St. Denis, and Henry II renouncing his Protestant creed there. These aren't just events in French history, but Western history, even world history.

We have, then, a mutual exchange as follows:

Art is to Culture, as the Visible is to the Invisible.

Tolkien knew very well, the secret that Scott Buchanan bluntly pointed out in his The Doctrine of Signatures: A Defence of Theory in Medicine. Why not go on to say, Art is to the Invisible, as Culture is to the Visible? Once that analogy is secured, the species of enchantment surrounding a made artefact like LOTR multiply and enhance each other, just as the analogies do. They reshuffle the logical syllogism. They take on a life of their own, and set up a feedback loop, which seems to be self-sustaining. They emerge out of lifelessness, and take on qualities compatible with life. All great art does this to a superlative degree. Great art which is also high, even more so. Some theological ancestors even argued that we ought to do this, for the glory of God.

“Lapis iste vel hoc lignum mihi lumen est”. "This stone or this wood is light to me". John Erigena wrote this, inverting the usual Platonic order of things, which put the Light first. Gene Wolfe, also, does the same thing in his famous line from the New Sun fantasy series, Citadel of the Autarch -

"Rain symbolizes mercy and sunlight charity, but rain and sunlight are better than mercy and charity. Otherwise they would degrade the things they symbolize."

Everyone can sense that an engagement Ring does more than just symbolize the beloved espousal with the ideal woman of their ideal dreams. In some important sense, the Ring has to be the woman. There has to be a betrothal or pledge, or there can be no wedding. There has to be a wedding, or there can be no Bride. At the same time, the Bride herself recapitulates all of the former and previous symbols. This kind of metaphysically "barbaric" (pre-modern) reasoning is found throughout in Scripture, particularly, in St. Paul.

Therefore being justified by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ: 2 By whom also we have access by faith into this grace wherein we stand, and rejoice in hope of the glory of God. 3 And not only so, but we glory in tribulations also: knowing that tribulation worketh patience; 4 And patience, experience; and experience, hope: 5 And hope maketh not ashamed; because the love of God is shed abroad in our hearts by the Holy Ghost which is given unto us. 6 For when we were yet without strength, in due time Christ died for the ungodly. 7 For scarcely for a righteous man will one die: yet peradventure for a good man some would even dare to die. 8 But God commendeth his love toward us, in that, while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us. 9 Much more then, being now justified by his blood, we shall be saved from wrath through him. Romans 5:1-9

St. Paul was so accustomed to using the enthymeme, that his spiritual logic gets missed. St. Paul argues from the hope of God in the heart, back to the certainty of heaven, just as he argues from God's great love in His son at the time of our need, forward to the destiny of full salvation. He inverts the two, into a Mobius loop.

Hope in the human heart, Christ, God's love, and salvation: all part of a Mobius loop to St. Paul.

Tolkien did not leave us in doubt, cloaking and eliding his enthymemes the way St. Paul does. We have his letters, and he spells it out for us. Tolkien, in his essay on Fairy Stories, clearly asserts that reality and language "co-arise", if I can use that term. One can extend the analogy - the made "artefact" and the author's mind, can be said to "co-arise". Which one is "inside" the other? Once one realizes that one can nest one syllogism inside the other one, all kind of possibilities erupt. If something is an "aspect" of the whole, then in some sense, it is a whole, and the greater whole, itself. A facet or aspect is not merely a part. It is a part that is also a whole, and even (somehow), the whole. It is a holon. That is the technical term.

For Tolkien, then, Reality is not so much a hierarchy, as a holarchy, or Holon. The Holon is the hierarchy. God rules, by virtue of His service. He also serves, by virtue of His ruling. Perhaps, after all, nesting Russian dolls are a better model for the universe than the rigid Totem pole. Saint Bonaventura put it this way -

That which is not compelled by the greatest, and that which is contained in even the smallest, is Divine.

Since God is structured in a perichoretic, Trinitarian way, the Universe models that by being structured as a Holon. It is not possible to dismiss an Art, which has taken Science, Religion, and Philosophy (some of the best known or possible), and transmuted them. Tolkien not only survives his critics, the attacks are absorbed into the living art of LOTR, and can even be transformed by them. We should expect it to happen. That is the way of "living" things, objects which are suffused with life, to assimilate and continue to grow.

Only under Man does Middle-earth make sense; it was all intended for him and will continue to be so until the world's end, when he shall encompass his own destruction - as he has so nearly done in the past, though never more than now - or reach the end of the world and stride into what lies beyond. Man's fate is so vast in its complication, ptomide and past, and so difficult to comprehend since we are part of it, that its contemplation has fallen into exegesis, and only now and then, as in the sayings of Christ, has its full nature been envisaged. It contains the root and the sum of all creation's drive, and this it is that makes it so entrancing, exhilarating and perilous. And such is Man: he would rather balance on the tightrope of his own creation, razor-thin and sagging in the middle, over the abysmal valley of his own folly, than walk in safety starting meadowlarks. It is in danger and in the times that most try his sould that he flourishes. He is born to trouble as the sparks fly upward. When his situation is most impossible, when he has lost all control, save perhaps over an individual being here and there, then he triumphs most... (p.100, William Ready, The Tolkien Relation